The Times - November 17 2000 - By Anjana Ahuna

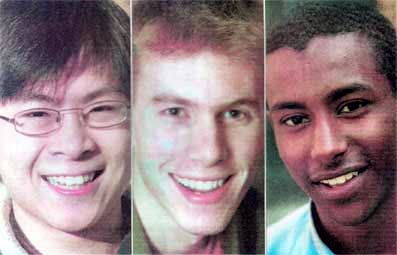

Three boys and their common Y chromosome inheritance - Alex Edmans, left, and Bennet Summers, centre, share a common ancestor of about 50,000 years ago with Amas Elturabi, right, of Sudanese origin; this is shown by the M158 marker, which is in the blood of all three.

The most profound achievement of the last century can be summed up in four letters: A, C, G and T. These letters- each the code for a chemical - that make up the sentences that make up the chapters that make up the book of human life.

The unique string of three billion letters that results in each person will spell out our individual's height, hair colour, and propensity for diseases such as cancer and arthritis. But the letters will also spell out something far more controversial - race. It is genes that colour skin, that determine the texture of hair. that shape the eyes, that sculpt the nose. This inevitable but explosive spin-off of genetics has sparked a division among those who cannot bear to close their eyes to the torrent of valuable information flooding before them, and those who fear a re-emergence of the concept of genetic superiority, which underpinned the horrors of Nazi Germany. After all, if science thinks it can extinguish or alter the genes that encode for disease, why not the genes associated with specific groups of people, such as the Ashkenazi Jews?

And if genes underlie physical differences, why not mental differences, too? The latter thesis still circulates among the fringe academics - most notably among those who subscribe to the ideas outlined in The Bell Curve, a 1994 book that implied black Americans were not as smart as white Americans, and that Jewish Americans and East Asians out-performed everybody else.

It is a fact, however, that some genetic diseases are shockingly discriminatory - cystic fibrosis, which can result in serious lung infections, afflicts mainly whites, while sickle cell anaemia, a blood disorder, predominantly affects blacks. Not to explore the genes involved, scientists protest, is to leave ethnic groups in the grip of disease for the sake of political correctness.

"We're not in the business of designing smart bombs to wipe out races," says Dr Spencer Wells, a population geneticist at Oxford University who has been studying the genes of different groups to trace how modern man wandered out of Africa and settled other continents. "People talk about the history of eugenics, and a lot of the early research in this country was pretty suspicious, but we are not doing this to divide people along racial lines. Our species has a single, shared history, and we ought to learn what it is."

The unfolding drama that is the Human Genome Project tells us this so far: 99.9% of the DNA of every person on the planet is identical. Roughly speaking, if you and your neighbour could compare your genetic blueprints, written as As, Cs, Gs and Ts - adenine, cytosine, guanine and thymine - the blueprints would be identical apart from every thousandth letter. So the spectrum of human variation - tall or short, black or white, blonde or auburn - is squashed into a tiny fraction of the genome.

But what we perceive as race does not make up the bulk of the 0.1% variation. Wells says: "You can find more genetic differences between two Africans than between an African and someone from the Outer Hebrides."

This is not an isolated example; the genetic variations within ethnic groups are wider than those between different groups. The genes of a pale Finn may match those of a dark South Indian more closely than those of a blonde Swede. Wells has logged around 200 genetic markers on the Y chromosome (for this reason the test can only be done on males) that correlate with different areas of the globe. Most people have multiple markers, suggesting migration and mixing throughout human history. And, ultimately, we all carry in our genes the traces of African ancestry. As professor Chris Stringer, from the Natural History Museum in London, puts it: "We are all Africans under the skin."

For that reason, Wells says geneticists do not subscribe to the concept of biology of race: "To me, race is a cultural construct. I put it another way: there is a genetic variation among geographical groups." He guesses that the characteristics we associate with race, such as skin colour, account for no more than a tenth of the variations between humans, which is 0.01% of our genetic make-up.

The people left Africa for other territories, they evolved different traits to adapt to their new environments. The most obvious attribute associated with race - colour - seems one of the most recent. The variation in skin colour may date back only a couple of thousand years, with paler skins emerging in colder regions to allow more efficient production of vitamin D from sparse sunlight. People living near the Equator evolved dark skins to protect them from the sun's damaging rays. Interestingly, the idea that pale pale skins reflect a more evolved race - a tenet of white supremacy - is bogus, population genetics reveal. It is most likely that when man appeared in Africa around 100,000 years ago, his skin was mid-brown. Paler and darker skins would have surfaced in tandem, according to where people settled.