A Question of Language

(Appendix F: The Genius of the Few by Christian and Barbara Joy O'Brien - Pages 340 - 352).

The Lords departed - The High assembly ended.

In it, the Lord had spoken at that time in

Eme-an - the language of Heaven:

Let us set up dwellings of cedar-wood.

The connection between Sumer and Crete is further accentuated by the discovery of the famous Phaistos Disc in a storage magazine at the north-eastern corner of the Minoan Palace of Phaistos in southern Crete, in 1908, by Dr Luigi Pernier, who was a member of the Italian archaeological mission.

Detail original

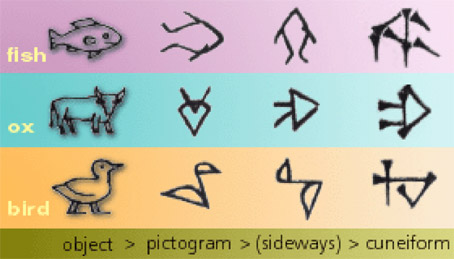

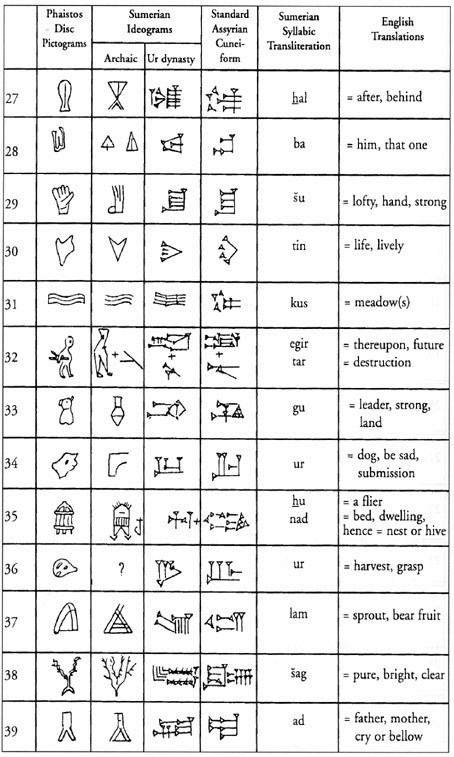

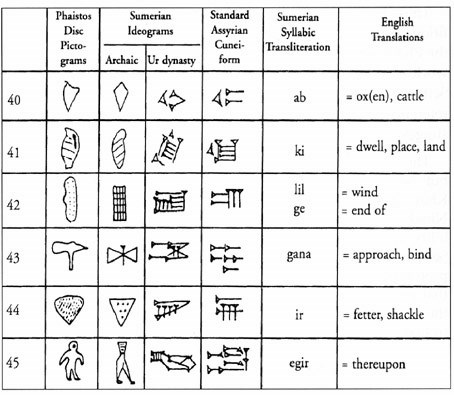

Evolution of the earliest picture language into cuneiform text. Each sign was accompanied by specific phonetic sound

It was a strange artifact - a baked clay disc, roughly circular, about six inches in diameter. It was inscribed, as shown above, with die-stamped pictographs in a spiral framework on both the obverse and reverse sides.

From the date of the destruction of the Minoan Old Palace, and the presence of Linear-A inscribed tablets in the same storage, it has been generally agreed that the emplacement of the Disc could not have been later than 1700 B.C. The disc, itself, of course, must be older - but by how much remains a mystery.

The pictograms, which are reproduced in the following pages are natural and well-drawn but, as yet, no satisfactory decipherment has been achieved.

Some of the pictograms bear a superficial resemblance to signs used in other Cretan scripts such as have been widely used for literary purposes in both the Near and Middle East from very ancient times. On the other hand, a single occurrence of an axe-head, has been compared to the Cretan double-headed axe, and used as an argument for a local origin.

But in this respect, it should be borne in mind that a similarly inscribed axe-head occurs on one of the upright monoliths at Stonehenge in England. These two diverse symbols were the starting points from which we have found it possible to develop the interpretations that follow - interpretations that are based in clear affinities between the Phaistos Disc pictograms and archaic Sumerian inscriptions from the earliest, vertical writings. However, by themselves, the two symbols carried only cursory conviction, but they served to open an avenue of rewarding research.Further study revealed that all forty-five individual Disc symbols - without exception - could be matched with standard, archaic Sumerian ideograms; some pairings having an out- standing degree of conformity. Furthermore, this comparison suggested that the Phaistos pictograms, with their rounded, pictorial style were original models for the cruder, and often angular, Sumerian outlines.

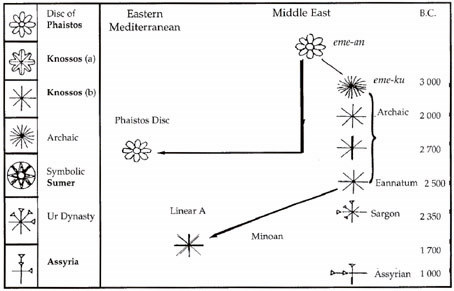

The correlations started with the first, and dominantly significant, sign at the centre of the primary side of the Disc, from which the spiral picture writing begins. This is the eight-petalled symbol- sometimes referred to as a Sun-sign - but considered, here, to be a 'divinity' or 'aristocratic' determinative which, in Crete, was closely associated with Zeus; and which, by comparison with a number of other dingir-like signs, widely-spread in space and time, pointed to a Sumerian connection.

The oldest of these clearly associated signs is the Sumerian Archaic, dating back to the end of the fourth millennium B.C.; but the most important, for the purposes of this study, is the third down in Fig. 10 - Knossos (b) (see page 343). In the chain of development in Sumerian writing, this symbol lies between the Sumerian archaic sign and that used during the Ur Dynasty some five hundred years later - and, in identical form, it was in use in Lagash in the time of Eannatum, in the later part of the first half of the third Millennium.

In Crete, the plain, eight-rayed, linear star is associated with the petalled variety of Knossos (a in fig. 10 below) - and is found, minus the central alignments, as the opening pictogram of the Phaistos Disc. In Sumer, the embellished eight-pointed star was the symbol of Ugmash (later to become Shamash, the Babylonian 'Sun God'). Almost invariably, it appeared above his head on bas-reliefs; and this correlation points to a connection - either in person or in position - to both Shamash and Zeus.

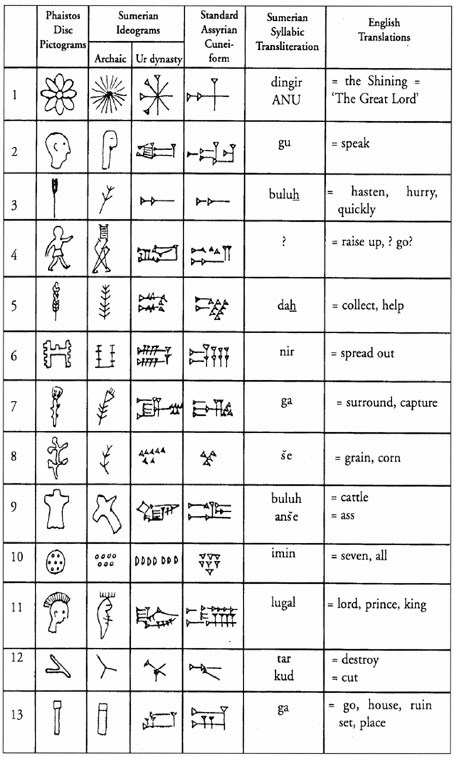

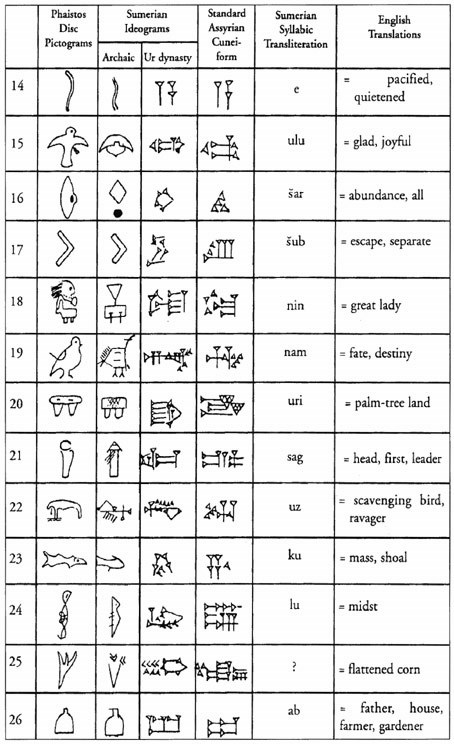

The comparisons between the Phaistos Disc symbols and the archaic Sumerian signs allowed us to compile later cuneiform equivalents, make standard transliterations, and suggest English translations. In the Tables on the following pages, the first column ascribes numbers for convenient reference, while the second lists the pictograms found on the Disc, in anti-clockwise order around the spiral framework. In the third column, we have placed what we consider to be the equivalent Archaic Sumerian pictogram, followed in the fourth column by the cuneiform ideogram into which the Sumerian pictogram would have developed by the middle of the third millennium, B.C.

It should be noted, that at some time between the Archaic and the Ur Dynasty phases, Sumerian writing changed from a vertical top to bottom order, to a horizontal left to right order. All signs were thus rotated, anticlockwise, through ninety degrees. This change is particularly easy to spot in numbers 2, 3, 6 and 7. In column five, we show the, so-called, Assyrian cuneiform into which Babylonian writing developed by the beginning of the first millennium B.C., and which is now used by scholars for transliteration comparisons. The sixth column shows the transliteration of the foregoing writing of columns 3,4 and 5 into Sumerian phonetic syllables; and the final column gives our determinations of the most likely English translations, based on the evidence of the emerging context.

The opening pictogram (at the centre - Side One), being a hierarchical determinative (or dingir), refers to the Shining One, or the 'Great Lord' - and, in the context of Cretan symbols, should signify the 'god' Zeus. The second pictogram (2) represents the Sumerian symbol gu which translates, unequivocally, to 'speak'. The third pictogram (3) - an arrow in both Sumerian and the Disc - qualifies the mode of the Lord's speech. For this the translation' quickly' has been chosen, but it could equally well mean, 'forcibly', 'directly', or 'penetratingly'. Thus the first phrase translates, credibly, from the Sumerian as: 'The Great Lord spoke quickly.'

The fourth pictogram is a graphic illustration of a man striding out, and its angular, archaic Sumerian equivalent gives a similar impression. The later cuneiform rendering has no known phonetic value but it is translated in the Kharsah Epics as 'raise up' or 'rise up', from which the more colloquial' get up and go' may be deduced. The Great Lord, therefore, was urging someone into action.

The Eight-rayed Divinity Symbol of Zeus (with its antecedents) and

the Developments of the Archaic Sumerian 'Divinity' Symbol

The start was extremely fortunate because, as all Sumerian scholars know, it is difficult (and, at times, impossible) to obtain a justifiable translation from an early, unilingual, Sumerian text without a knowledge of the context. In this respect the Phaistos text is helpful to the translator - near the beginning, it refers to 'com','oxen' and seven lords; and when the syllable sub appears, which meant I escape', the context of the piece falls into place. The 'seven lords' bring to mind the Council of Seven of the Anannage and of the Archangels; and the number occurs, as has been seen, in a number of other hierarchies of the Shining Ones.

Because of this piece of good fortune, we believe that the translation which follows is broadly correct, but, of course, it cannot be guaranteed in every detail because of the shortness of the text, and the limited number of pictograms available. The multiplici- ty of meanings assigned to individual Sumerian ideograms, and the spread of phonetic values, combine to make it unlikely that there can be a unique solution to a text of this kind. In the poet- ic style, outlined below, the numbers at the right-hand side refer to those assigned to the Phaistos symbols.

These lines are notable in their similarity to the peculiar, repetitious style and context of the Kharsag Epics; and it may be that the Phaistos tale was originally part of a collection describing the world-wide activities of the Anannage in an undisclosed farming Settlement which has all the hall-marks of another Kharsag. The reference to our Great Lady [? Ninkhaisag] in Line 10, however, suggests that the poem may be referring to Kharsag, itself.

The Great Lord may have been Zeus in the context of Crete, but he was undoubtedly Father Enlil in the context of the Kharsag Epics; and the Great Lady was none other than Ninkharsag, wife of Enlil and the Mother of Life, whose responsibility would have been the fertility of the plantations at the Settlement. She was the Great Mother who was to become the prototype for all the Earth Mothers in the deifying mythologies that grew up in the wake of her departure. As suggested earlier, the Seven Lords were the Anannage Council of Seven that controlled the destinies of Kharsag.

| A PASTORAL DISASTER - Side 1 | |

| The Great Lord spoke quickly: 'Go and collect helpers spread out in the cornfield, and surround the oxen of the Seven Lords.' |

1-2-3 4-5 6-7-8-9-10-11 |

| The Great Lord spoke quickly: 'Go! - before the corn is destroyed go and collect helpers for the Seven Lords. They [the oxen] must be pacified. |

1-2-3 8-12-13 4-5-10-11 10-14-15 |

| The escape could destroy the harvest [abundance] (produced) by our Great Lady: the escape of the oxen is threatening the land - the oxen of the Seven Lords. They must all be pacified.' |

12-16-17-18 9-17-19-20 9-10-11 10-14-15 |

| The Headman ran. The stampeding oxen of the Lord(s) had streamed out and escaped. 'They must all be pacified - (for) the oxen went as a herd. Spread out into the cornfield and surround the oxen of the Seven Lords. They must all be pacified.' |

4-21 17-13-3-22-9-11 10-14-15 13-23 6-7-8-9-9-10-11 10-14-15 |

| The Headman ran. The rampaging oxen of the Lord(s) stampeded and escaped. In their midst, the birds scavenged. |

4-21 17-13-3-22-9-11 22-24 |

| The Great Lord went (to learn) the fate of the (oxen) of the Seven Lords; the ox-herder hurried after him. The corn of the Seven lords was being trampled down. |

1-13-10-11 26-27-28-4 8-12-28-10-11 |

| They had rejoiced over that grain but the oxen (?) of the Great Lady (obscured) of the Council had escaped. |

8-14-15 17-18-10-11 |

| On the Heights, the lively oxen were all in the fields and meadows; the running herd was destroying the (harvest) of the Seven Lords. |

29-30-9 10-26-1-9 23-27-32-10-11 |

| The Leaders were saddened; the ox-herder in the meadows was saddened - for all the bee-hives were overturned. The Seven Lords hurried to stop the stampede into the Father's meadows |

33-34-34 26-31-34 10-27-35 17-4-5-10-11 |

| Side 2 | |

| The ravagers ruined the saddened land: the cornfields of the Great Lady were ruined. The crushed cornfields had been ready for harvesting - the lofty, bright, fertile cornfields of the Mother. |

22-13-8-18-11 26-13-8-18-11 26-17-25-36-37 29-26-38-34-39 |

| The bee-hives were overthrown and (lay) broken in the fields - in the Father's fields and meadows: the Father's corn was destroyed. |

35-17-13-26 26-31-16 8-17-16 |

| The powerful oxen were rampaging in the midst of the lofty, bright fields (farm) of the Mother. The Father's fields had been fertile; the strong helpers were saddened. |

22-14-33-9 29-26-38-34 27-31-34 5-29-34 |

| The lofty fields were bright and fertile - the oxen ran through the plantations of the Lord. |

29-26-38-34 4-9-37-11 |

| The corn of the Great Lady was fated to be flattened by the herd: the herd went into its midst - escaped into the midst of Achaia. |

23-25-19-8-18 4-23-24 17-20-24 |

| The corn and the bee-hives had been rich in that place. The Great Lord ran to the ravaging oxen after (they had destroyed) the tranquility of the Lords; but they had crushed the corn and the beehives. |

8-41-35-34 4-1-22-9 |

| The surrounded ravagers bellowed in the midst; as those who had gone to help approached the escapers in the fields. And as the herd was flattening the grain, those who had gone to help shackled the escaping cattle. |

|

| All the ranks of bee-hives in that place were ravaged by the bellowing oxen. Thereupon, the Lords captured the culprits the oxen in the cornfield and in the meadows behind the House of the Mother of the Seven Lords. |

In the Kharsag Epics, there is mention of honey, but not of bee-hives; however, the possibly paronomastic phrase of pictogram 35 - hu-nad - meaning 'a nest, or bed, for fliers', combined with the skip-like shape of the sign, appears to be unequivocal. Hu-nad was a bee-hive.

After the destruction of Kharsag, and the move of the Anannage into Mesopotamia, the Sumerian term uri (seen in pic-togram 20) was used to designate the land of Accad (Akkad). A liberty has been taken in the last line of the fourteenth stanza where uri has been translated as 'Achaia', the original name for the district in which Kharsag was established. There is substantial evidence that the name Achaia was carried to Mesopotamia by the Anannage, where it was subsequently corrupted into Accad.

We are very much torn between attributing the story of the Phaistos Disc to activities on the Lasithi Plateau in Crete, and attributing it to the original Kharsag. It is written so much in the style of the Kharsag Epics, with references to the Father and the Mother, that it would seem, at least, to have been written by the same chronicler. Two lines are particularly reminiscent of the Epics:

'In their midst, the birds scavenged.' and

'On the Heights, the lively oxen ...'

In the Kharsag Epics, it was stated:

'The bird discovers the sown field.' and

'... its fields were full of lively horns;

the vigorous young animals raced about the Heights."

'The Heights' were frequently mentioned in the Epics.

On balance, we would consider it likely that the Phaistos Disc is a Cretan artifact carrying a story which originated in Kharsag, and had been written in the original pictograms of the proto-Sumerian language of erne-an.

At first sight, it may be thought that this was a very trivial tale to be recorded on such a tablet as the Phaistos Disc; but it has to be realised that the loss of a harvest in the first years of a Settlement could have been a very serious matter, both for the Anannage and for the tribes-people that they were supporting. On the other hand, it is also true that the importance of the Disc is of our own making; and there is no evidence that the scribe who conceived it, intended it to be other than, for example, a child's reading primer.

We have to remember that we, in Britain, have our own apparent trivia that have repeatably been published for centuries as Nursery Rhymes. One such has the same theme as the tale on the Phaistos Disc:

Little Boy Blue come blow your horn!

The sheep's in the meadow, the cow's in the corn!

Where is the boy that looks after the sheep?

He's under a haycock, fast asleep!

No-one knows the age of our older nursery rhymes nor, indeed, where their origins lay. But, as so much of Western culture has stemmed from Sumeria, it is amusing to speculate whether the Phaistos Disc might record the antecedents of 'Little Boy Blue'.

[And here, it would be remiss of us not to mention that the above interpretation of the Phaistos Disc was submitted by us to a prestigious scientific journal, and turned down without serious comment. It was obvious that its referee had no knowledge of Kharsag and its subsequent history.]